America’s Top 10 Greatest Navy Explorers

Reprinted with permission from the October 2009 issue of VFW magazine

Death-defying exploration of the globe’s perilous uncharted regions may be mostly a preoccupation of the past, but its leading practitioners — modern and centuries gone by — are no less deserving of respect and recognition.

Throughout its history, the U.S. Navy’s principal function — war fighting — has often yielded exploration and discovery as byproducts. Cases in point are the brave and tenacious explorers presented here.

These men made especially significant contributions to our understanding of the ocean depths, the expanse of space, the capacity and capability of vessels ranging from leaky wooden ships to high-tech spacecraft , and the limits of human endurance.

This is my list of the “Top 10” in U.S. naval history. See if you agree that they rate this exploration standing. They appear in chronological order, not by precedence of achievement.

Robert Gray - 1792

Lesser known for his naval service than for his exploration of the Pacific Northwest, Gray served in the Continental Navy during the American Revolution. He also commanded the privateer Lucy during the quasi-naval war with France in 1799.

Under the auspices of a Massachusetts trading company, Gray and John Kendrick set out from Boston for Oregon in 1787. After trading with natives for sea otter pelts, they set their sights on Asia, where they traded for tea and other products.

Continuing his journey west, Gray then became the first American merchantman to sail around the world. But his crowning achievement came during his second trip to the northwest in 1792, when he discovered what he believed to be “the great river of the West,” naming it “Columbia Rediva.”

Gray never returned to Oregon, but his momentous discovery laid the groundwork for America’s claim to the rich resources of the Columbia River territory.

Charles Wilkes - 1838-42

He is best known in naval history annals for his role in “The Trent Affair” in the American Civil War. But in world exploration circles, Wilkes is forever connected to his Wilkes Expedition, formally known as the U.S. South Seas Exploring Expedition (1838-42).

Appointed in 1830 to the Navy’s Department of Charts and Instruments, he was an early developer and user of astronomical instruments.

In 1838, he set sail on the exploring expedition (the Ex Ex, as it was known then) in the Vincennes with six other vessels that carried the nation’s leading natural history scientists and artists.

Four years and almost 87,000 miles later, the expedition returned to the U.S. with thousands of plant and animal specimens and other artifacts, the largest such collection ever gathered up to that time. It later served as the basis for the U.S. National Herbarium, the U.S. Botanic Garden, and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

Wilkes also is well-known for his 1841 exploration of Puget Sound and the Columbia and Sacramento rivers in the American West. All told, the expedition explored most of the world’s continents, including the Antarctic coast.

William Lewis Herndon - 1851

How many Naval Academy plebes know the origin of the name attached to the granite obelisk they must climb as a rite of passage to becoming third class midshipmen?

The monument was named for an explorer who charted much of the Amazon River basin. Herndon’s Amazon expedition in 1851 with Lt. Lardner Gibbon was ostensibly to assess the region’s commercial value. But the Navy’s superintendent of charts and instruments, Matthew Fontaine Maury, had secretly ordered the duo to determine the viability of establishing a U.S. colony there.

On his return to the U.S., the Mexican War veteran (he served aboard the brig Iris off Vera Cruz during 1848) wrote the two-volume Explorations of the Valley of the River Amazon. It is still widely cited as an authoritative source on the natural resources of the region. Herndon went down with his ship during a Caribbean cyclone in 1857.

Robert E. Peary - 1909

Credit for “discovering” the North Pole is still being debated in Arctic exploration circles more than a century after Peary claimed to have been the first there on April 7, 1909.

On that date, he wrote in his diary, “The Pole at last,” when he and five of his men — black American Matthew Henson and four Eskimos — ostensibly reached their goal. Those immediately questioning Peary’s conquest included Dr. Frederick Cook, who had claimed the distinction himself a year before.

A 1990 study commissioned by the National Geographic Society, using photogrammetry to analyze Peary’s expedition photos, surmised that shadows cast in the images proved his claim.

In 1991, a U.S. Naval Institute symposium never reached a consensus, despite a substantial monetary offer from Peary family members for solid evidence that would disprove the claim. No money changed hands.

This aside, Peary earns a place on this list for his pioneering Arctic exploration and for developing “the Peary system,” a supply and support structure that proved invaluable in his various expeditions from 1886 to 1909. Congress promoted him to rear admiral in March 1911.

Richard E. Byrd - 1929

While evidence surfaced in 1996 that Byrd had falsified his official 1926 report on the flight in which he and pilot Floyd Bennett claimed to be the first to fly over the North Pole, he is still credited with several aviation and exploration milestones.

To aid in navigation over the open ocean, Byrd developed drift indicators and bubble sextants for aircraft, thus leading to his participation in planning the flight path for the Navy’s transatlantic crossing in 1919.

In summer 1927, he made a transatlantic flight himself and in November 1929 made the first flight over the South Pole. Byrd triumphantly returned to the U.S. in 1930 and was awarded the Gold Medal of the American Geographical Society.

In all, he made five expeditions to Antarctica, culminating in the establishment of permanent bases at McMurdo Sound, the Bay of Whales and the South Pole. For his efforts, Byrd was awarded the Medal of Honor (before it was restricted to recognizing valor in combat only).

During WWI, he was commander of the Navy’s flying boat station in Nova Scotia. In WWII, he served on special missions in Europe and the Pacific. He was a rear admiral.

Edward L. Beach, Jr - 1960

The Cold War was a cat-and-mouse game of one-upsmanship, and Ned Beach (as he was known to his friends) one-upped the Soviets in spectacular fashion.

From February to April 1960, he was the skipper of the USS Triton (SSRN-586) during the nuclear-powered submarine’s submerged circumnavigation of the Earth. This was the first such voyage in history and one that broke a submerged speed record that still stands. It was actually his idea, as he recalled in the last interview before his death. “Finally, I got an idea. We’ll do a stunt. We’ll go around the world.” And what a stunt it was.

During WWII, he served aboard three subs, earning the Navy Cross. Beach was the naval aide (1953-57) to President Dwight D. Eisenhower and became a successful author. But he was most proud of his feat in the Triton.

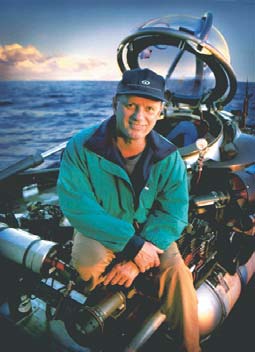

Don Walsh - 1961

The “Deepest Dive” happened in 1961. Only unmanned remotely operated vehicles have matched the feat since then.

While the rest of the world focused on the space race, the Navy was looking inward, to the uncharted waters of the oceans’ depths. In this case, it was the Challenger Deep in the Pacific Ocean’s Marianas Trench near Guam.

With Swiss explorer Jacques Piccard, Walsh set the manned deepdive record at nearly 11,000 meters (36,000 feet)—with the pressure being more than eight tons per square inch at that depth.

In an interview, he referred to the expedition as “just another day at the office.” Walsh is still diving today at age 77, leading expeditions to the wrecks of, among others, RMS Titanic and the German battleship Bismarck. And his exploration of Antarctica led to a mountain ridge on that icy continent being named after him.

Walsh was executive officer of the submarine Bugara off Vietnam in 1963.

M. Scott Carpenter - 1962-65

One of the original Mercury astronauts, Carpenter also was an aquanaut, the first human to explore both inner and outer space. He flew the Aurora 7 in the second manned orbit of the Earth on May 24, 1962.

Following that mission, he consulted on the design of the lunar module for the Apollo project. Three years aft erhis orbital flight, he went on leave from NASA to participate in the Navy’s Man-in-the-Sea Project as an aquanaut in the SEALAB II experimental endurance program. He spent 30 days 205 feet below the surface off the coast of La Jolla, Calif., in 1965.

In a recent interview, Carpenter explained the purpose of sea exploration: “In a way, it’s still defense-oriented; but we’re trying to defend the planet now, instead of just this country.”

Off Korea in 1951-52, he flew P2V Neptunes on recon missions with Patrol Squadron 6. Later, he operated out of Adak, Alaska, and Guam.

Neil Armstrong - 1969

If you’re old enough, you must remember the grainy television broadcast of Armstrong stepping onto the floor of the Moon’s Sea of Tranquility, mesmerizing the inhabitants of Earth on July 20, 1969.

With his first words from the lunar surface, “That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind,” he became a hero to youngsters around the world.

(Armstrong also was command pilot of Gemini 8 in 1966, a mission highlighted by the first docking of two vehicles in space.)

A naval aviator in the Korean War, he flew 78 missions between Aug. 22, 1951, and March 5, 1952, as part of Fighter Squadron 51, Air Group 5, aboard the USS Essex. He was shot down once.

Robert Ballard - 1985

Few explorers have covered as much of the world’s sea floor as Ballard has. And none has gained more fame and fortune for those expeditions. While he has dived on some of the most famous shipwrecks in sea history, he was the first to locate, study, and film the remains of the Titanic, the passenger liner sunk by a collision with an iceberg on April 15, 1912

The expedition — to depths of 2.5 miles — was funded by the Navy, which mandated that Ballard locate the wrecks of the mysteriously sunken nuclear-powered submarines Scorpion (SSN-589) and Thresher (SSN-593). Finding the Titanic in late summer 1985 was a bonus. Ballard also was an outspoken critic of later operations that salvaged artifacts for profit from the sunken liner.

He served in the U.S. Navy from 1967 to 1970, and was assigned to the Deep Submergence Group at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts.

‘Celebrate and Honor’

All these Navy explorers accomplished amazing feats. But sadly, today, their names are lost to history in a society that seems to place little value on, or celebrate, such achievements.

As Navy Vice Adm. Melvin G. Williams, Jr., commander of the U.S. 2nd Fleet, recently said regarding the centennial of Peary’s North Pole expedition, “We should celebrate and honor the exploits of heroes.”

Fred Schultz is managing editor of U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings and consulting editor for Naval History

E-mail magazine@vfw.org

Back to top