Exploration through the Ages

Reprinted with permission from the Marinerís Museum, Newport News, VA (www.mariner.org)

Editor’s note: The Mariner’s Museum, located in Newport News, Virginia has graciously allowed the Mariners Weather Log to highlight their current exhibit, "Exploration through the Ages." This expose will be offered in three parts throughout this year’s MWL issues. In the first installment, we will look at "Changing View of the World." Look for other installments on the "Tools of Navigation" in August, and finally, "The Great Exchange" in the December issue of the MWL.

— thanks once again to our friends at the Mariners Museum -- Luke

Exploration has been a part of civilization for thousands of years. Retrace the steps of the great explorers fromthe far-off days of ancient Egypt, to 19th century expeditions of the harsh North and South Pole, and beyond.

Changing View of the World

The Development of Map-MakingMaps are often defined as regional representations of the earth or heavens. They are much more than that though. Maps measure distances, provide direction, and depict natural and political boundaries. They show how the world is laid out at a particular time. They also show how much individuals associated with mapmaking knew about the world at that time. For these reasons, maps are excellent tools to learn how the world has been perceived throughout history.

European maps from the Age of Exploration reflect what was known, what was unknown, and even what was sought after. Some maps feature well known areas such as European colonies or regions frequently visited by Europeans. These are rendered with both precision and accuracy, even by todayís standards. Some maps feature unknown or largely unexplored areas. These may feature glaring inaccuracies such as missing pieces of coastline or empty expanses. Some maps feature mythical areas that Europeans had heard of or simply supposed existed. These feature fantastic locations or geographic features.

The overall quality of maps advanced dramatically during the Age of Exploration. Cartography, among other sciences, had developed rapidly since the Renaissance. Additionally, Europeans were sailing further and further from their own shores and returning from their voyages with accounts of the distant lands they had reached. As the number of voyages increased, so did the knowledge of these lands. By the 1500s, European mapmakers were producing material that, although not accurate by todayís standards, represented the world well enough that a modern viewer could recognize it. In a sense, these maps from the Age of Exploration provide a link between that world and the modern world.

The maps featured in this section are from the rare map collection at The Mariners' Museum. They are just a few items that were selected to illustrate how Europeans perceived the world during the Age of Exploration.

The rare map collection at The Mariners' Museum includes 1,287 maps ranging in dates from 1540 to 1899. Maps in this collection feature hundreds of geographic locations and vary in specificity from a particular city to the entire world. There are also celestial maps depicting the planets and constellations. This collection includes maps by prominent names in the history of cartography such as Joan Blaeu, Abraham Ortelius, Nicolas Sanson and Gerard Valck.

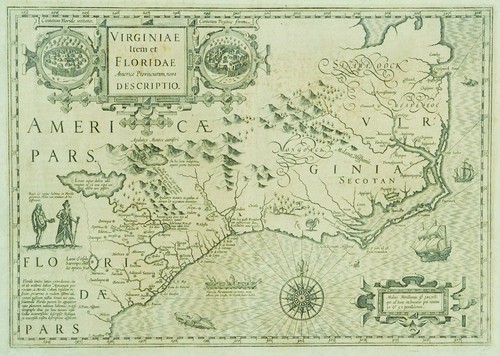

1619

Virginia Item et FloridaThis map (Map 1) illustrates the extent of European knowledge in regard to the eastern seaboard of North America in the early 17th century. The "Virginia" it depicts is the English vision of Virginia prevalent at the time, namely modern day North Carolina, home to the failed English colony of Roanoke. While the geography of North Carolinaís Outer Banks is relatively accurate, areas north and south of this area are generally less accurate. The southern portions of modern day Virginia are visible in the upper left of this map and show a very wide waterway that does not exist in reality.

Meanwhile, the Spanish territory of "Florida," which included most of modern day Florida along with the modern states of Georgia and South Carolina, is hopefully depicted as a land of gold-bearing mountains and large inland lakes. The area had been explored in the 16th century by Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto, but several attempts to colonize the region had ended in failure.

Despite some generally questionable geography, this map includes some interesting vignettes depicting native flora and fauna. Several whales are shown offshore, along with what appears to be a rather large turkey. Also of note are period depictions of the native inhabitants of the eastern seaboard. In 1619, the Native Americans of this region were still considered rather mysterious back in Europe, and a map like this would help European viewers picture both the lay of the land and its inhabitants.

Map 1. 1619 Virginiae Item et Floridae, Gerard Mercator, Amsterdam, 1619, From The Library at The Mariners' Museum, (MSm0208).

(Click image to enlarge)

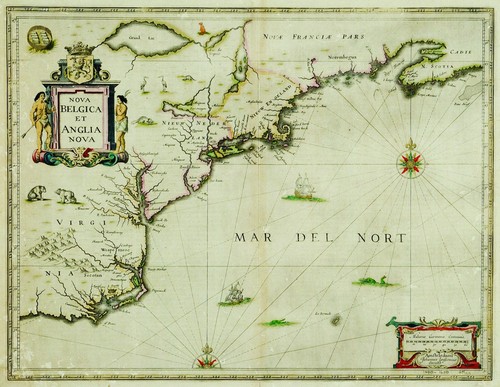

1610-1640

Nova Belgica et Anglia NovaWhen compared with the earlier map depicting North America in 1619 (MSm0208) , this map (Map 2) by noted Dutch cartographer Jan Jansson shows a great expansion in Europeís knowledge of the area after only thirty years. Modern day Virginia is accurately depicted, although the long, tapering Eastern Shore of todayís Virginia and Maryland is badly misrepresented. Meanwhile, the Dutch colony of New Netherlands (containing much of modern day New York State) is very well illustrated, including details on the interior. Such detail reveals that Jansson likely had access to the maps and reports of returning Dutch explorers to the area; notice the lack of thorough documentation for the interiors of the English territories of Virginia and New England.

Though the map includes the French territory of New France (modern day Maine and parts of Canada), it is revealed that the area was still shrouded in mystery; interior details are lacking, and there is only a tantalizing image of a single, large inland sea representing one of the Great Lakes. Further exploration was needed to fill in the blank portions of the map!

In an obvious reference to the important fur trades of New France and New Netherlands, a beaver is depicted on the map, roughly in the region of modern day Pennsylvania or upstate New York. Beaver pelts were part of an important and complex trade system worked out between the French, English and Dutch settlers of the area.

Map 2. 1610-1640 Nova Belgica et Anglia Nova,

Jan Jansson, Amsterdam, 1650, From The Library at The Mariners' Museum,

(MSm0132).

(Click image to enlarge)

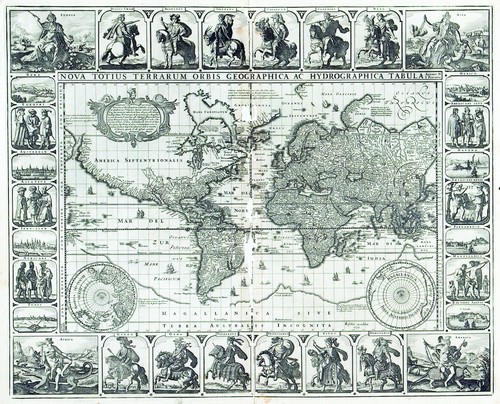

Strait of Anian - 1652

Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Geograohica ac Hydrographica TabulaThis map (Map 3) illustrates something that Europeans knew little about during the Age of Exploration: the Strait of Anian. The Strait of Anian (Strete of Anian on this map) was depicted as a channel between northeastern Asia and northwestern North America. Europeans hoped that it would lead to a northerly marine route connecting the Pacific and Atlantic Oceansówidely known as the Northwest Passage.

Map 3. Strait of Anian - 1652 Nova Totius

Terrarum Orbis Geographica ac Hydrographia Tabula, 1652, Nicholas Visscher,

Amsterdam, The Library at The Mariners' Museum. (MSm400)

(Click image to enlarge)

The Strait of Anian was first mentioned in a 1562 pamphlet published by the Venetian cartographer Giacomo Gastaldi. Within five years, it was featured on maps. Northwestern and northern North America was largely unexplored so there was very little knowledge of the area at that time; European sailors surmised that the Strait of Anian might be the entrance to a northerly route between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

Therefore, on maps like this, the interior of northern North America was not rendered in great detail. Such a route would have spared sailors the long and dangerous southerly voyage around the southern tip South America, making for quicker and easier commercial voyages to and from Asia.

Origins of the name Anian are unclear. However, a common belief is that it came from Marco Polo, who mentioned the islands of Ania in his narrative account of his travels throughout Asia in the 13th century. The name, Strait of Anian, appeared on maps until the 18th century. In 1768, the name appeared on a map as the Bering Strait (as it is known today), named after Vitus Bering, who explored that area and the Arctic Ocean for Russia in the 1720s and ’30s.

Although the strait’s name changed over time, the European quest for a northerly marine route remained constant. Such a route was not successfully sailed until 1906, when Roald Amundsenís threeyear voyage from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. Amundsen, a Norwegian explorer, entered Baffin Bay in 1903 and reached Nome, Alaska, in 1906. This route was fraught with shallow and narrow passages and, ultimately, was not viable for large scale, commercial travel.

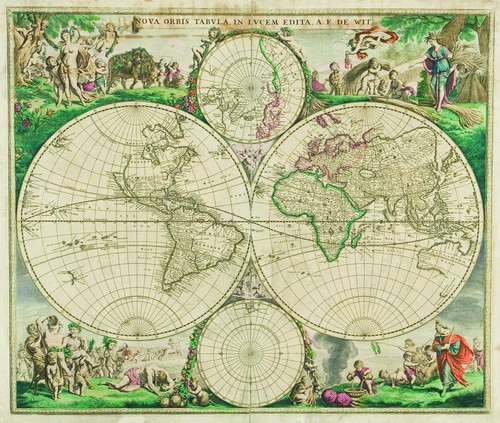

California as an Island

Nova Orbis TabulaThis map (Map 4)illustrates something that was not known during periods of the Age of Exploration: California was actually part of the North American mainland. When the Spanish explorer Hernan Cortes landed on the southeastern coast of the Baja California peninsula in 1535, he supposed that it was part of a larger island.

Map 4. Nova Orbis Tabula Nova Orbis Tabula, 1688, Frederick

de Wit, Amsterdam, The Library at The Mariners' Museum.

(MSm4)

(Click image to enlarge)

With orders from Cortes, Francisco de Ulloa explored both sides of the Baja California peninsula in 1539. It was he who correctly determined that it was not an island. Accordingly, maps of the regions depicted California as part of the mainland for the remainder of the 16th century.

In the early 17th century, Father Antonio de Ascension wrote about a 1602 voyage by another Spanish explorer, which revealed that California was, in fact, an island. Ascensionís account was published as part of a larger work and, within a few years, his errant theory that California was an island began to take hold.

In 1622, a Dutch atlas was published depicting California separate from the North American mainland. By the 1640s, most of Europeís major cartographers were publishing maps showing California as an island. This persisted for over 100 years.

Over time, knowledge of the area increased and solid evidence to the contrary was relayed back to Europe. By the 18th century, some maps began showing California as a peninsula. It was not until 1747, however, when Spainís King Ferdinand issued a decree proclaiming that California was not an island that this issue was officially settled.

The Southern Continent - 1694

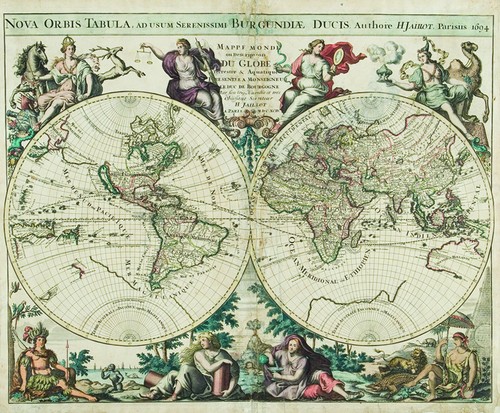

Nova Orbis Tabula Ad Usum Serenissimi Burgundae DucisThis map (Map 5) reflects something Europeans did not know in terms of the world: the shape of Antarctica. By the date of this mapís publication, 1694, sections of Antarcticaís coastline were often featured on maps. Such information, however, was inaccurate because it was based on speculation or sailorsí errant sightings.

For hundreds of years, people had speculated that a southern continent existed to balance the earth. This belief dates as far back as the second century when Ptolemy suggested it in Geographia. In the 1500s, sailors blown off course by storms while rounding South America’s Cape Horn recorded sighting land, which they supposed was the southern continent (or Terra Australis or Australe as it was often referred to on maps). More likely than not, these sailors actually saw one of the islands east of Cape Horn.

Because of the scarcity of reliable information about this region, it was represented in various sizes and shapes throughout the Age of Exploration. Antarctica, as we know the southern continent today, was officially sighted in 1820, and it was then that accurate mapping of it began.

Map 5. Nova Orbis Tabula Ad Usum

Serenissimi Burgundae Ducis, 1694, Charles Hubert Alexis Jailot, Paris, The

Library at The Mariners' Museum. (MSm2)

(Click image to enlarge)

1700-1750

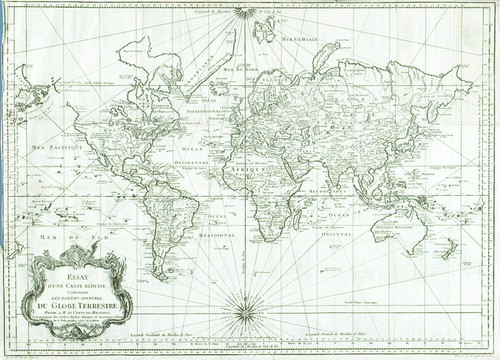

Essay D’une Carte Reduite...By the mid-eighteenth century, European cartographers were finally able to produce reasonably accurate maps of the entire world. In 1749, French cartographer Jacque Nicolas Bellin produced one of the finest, showing correct details for most of the continents, including full and accurate depictions of South America, Europe and Africa (Map 6). His illustrations of these places show an amazing amount of detail and show that Europeans had fully explored the coasts of these places, though interior details of inland locations were still missing for South America and Africa.

But notice that there was still work to be done for explorers and cartographers; the west coast of North America is either missing or riddled with inaccuracies. The modern day state of Alaska is not shown, and the northwest territories of modern day Canada are still a complete mystery to Bellin. Conversely, the Pacific coast of Russia was not entirely understood or explored yet either. The continent of Australia has finally taken its familiar form in Bellin’s map, although he shows that further explorations were needed to fill in the missing southern coast.

The world beyond the comfort of Europe was finally available with the publication of accurate world maps in the mid and late 1700s. As Europeans’ knowledge of the globe expanded, the number of unexplored, mysterious or terrifyingly unknown lands on the map shrank.

Map 6. Essay D'une Carte Reduite...,

Jacques Nicolas Bellin, Paris, 1749, From The Library at The Mariners'

Museum, (MSm0765).

(Click image to enlarge)

1719

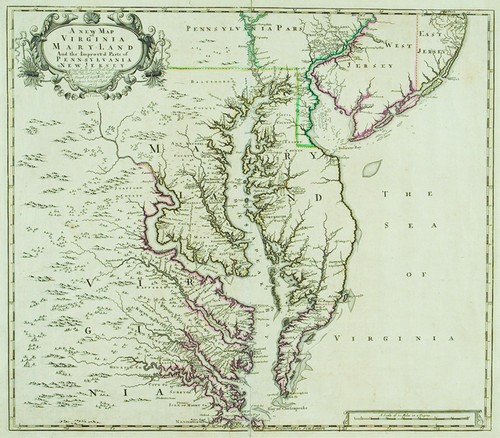

A New Map of Virginia, MarylandThe coasts of Virginia and Maryland take on their familiar shape in this rather accurate English map of 1719 (Map 7). Though the territories beyond the heads of the James and Potomac Rivers had yet to widely open themselves to English explorations, the heavily populated coasts are extremely well depicted. English settlers had, by this time, fully explored the Chesapeake Bay, making it the home to many a plantation or small anchorage.

Map 7. A New Map of Virginia, Maryland, John

Senex, 1719, From The Library at The Mariners'Museum, (MSm0203).

(Click image to enlarge)

Compare this map to Jan Jansson’s 1650 map (Map 2) of roughly the same area, and notice how far European knowledge of Virginia and Maryland’s Eastern Shore had progressed. It was no longer a blocky appendage hanging below the territory of New Jersey, but a reasonably accurate depiction of itís actual, tapered shape. At the time of this mapís creation, the modern state of Delaware was occasionally considered part of the larger colony of Pennsylvania. The borders of Delaware are rather poorly defined in this map, perhaps reflecting this.

The eighteenth century saw a great deal of advancement in Europeanís knowledge of the world, and this map certainly reflects a much more accurate view of North America’s eastern seaboard. But beyond the coast, the English still had a great deal of mapping to do; notice that this map does not include any settlements past the Tidewater of modern day Virginia.

Cibola and Quivira - 1722

This map (Map 8) illustrates something that Europeans sought during the Age of Exploration: the cities of Cibola and Quivira, two of the legendary Seven Cities of Gold. On this map, Cibola and Quivira are placed in present-day Arizona and Colorado respectively.

Map 8. Carte du Mexique et de la Floride des Terres

Angliouses et des Isles Antilles, 1722, Guilaume

Delisle, Amsterdam, The Library at The Mariners'

Museum. (MSm166)

(Click image to enlarge)

Spanish lore has it that when the Moors invaded Spain in the eighth century, seven bishops fled to far away lands to protect treasured religious relics, and founded the cities of Cibola and Quivira. In the years that followed, the legend grew, indicating that each of the seven bishops had founded a city, and that these seven cities enjoyed incredible wealth.

Europeans, the Spanish in particular, actively searched for the Seven Cities of Gold as they began exploring North America. They did so though without an exact understanding of what they were looking for; their knowledge was unreliable, based on misinterpretation, speculation, or outright misinformation. Consequently, Cibola and Quivira are placed in various locations in the American Southwest on certain maps into the early 18th century.

Back to top