Yemen Sees Unprecedented Tropical Cyclone Double-Whammy

By Andrea Thompson Senior Science Writer for Climate Central

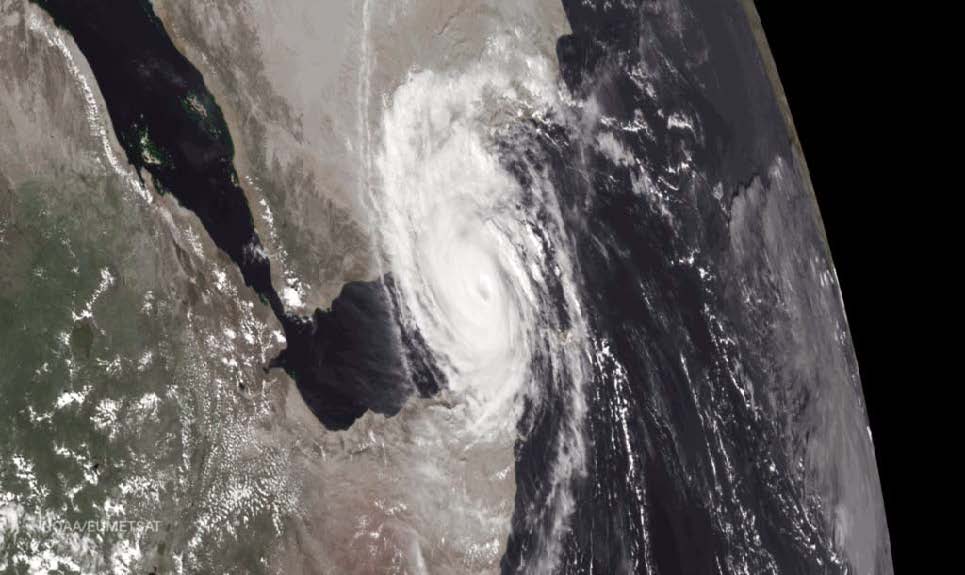

This photo shows a high definition visual of Cyclone Chapala November 1, 2015. Chapala made landfall on Tuesday November 2nd west of Mukalla. Right behind it you can see the formation of Cyclone Megh, which will make a direct hit on Yemen’s Socotra Island November 8th and make a final landfall in mainland Yemen on November 10th. (Image: NOAA/EUMETSAT)

This year’s hurricane season in the Arabian Sea was already one for the books, thanks to just one storm, Cyclone Chapala. This cyclone became one of the strongest ever recorded there and the first hurricane-strength storm known to make landfall in Yemen this past November 3nd, 2015.

Now the arid country has had an unprecedented back-to-back strike, as Cyclone Megh made landfall near the major port city of Aden early Tuesday morning, November 10th.

This marked the first time storms in such quick succession have been recorded in the Arabian Sea at this time of year. The unheard-of activity may have received a boost from El Niño and recent research has suggested that both changing levels of air pollution and climate change could alter tropical cyclone activity in the region.

While Megh wasn’t as strong as Chapala when it made landfall, having weakened to tropical storm strength, it was still expected to dump considerable rains on the region. As the up to 24 inches of rain Chapala dumped in some areas made clear, such rains can lead to extensive, dangerous flooding in such a dry landscape.

Megh formed just two days after Chapala slammed into Yemen, a considerable surprise given how few storms the Arabian Sea region typically sees. The basin may only see one or two tropical cyclones in a whole year, compared to other basins, which range from five to more than 20 in an average season. (Tropical cyclone is the generic term for hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones, different names for the same phenomena.)

Cyclones are less common in the Arabian Sea than in other ocean basins because, despite very warm waters that would otherwise provide ample fuel for storm convection, winds in the region are generally hostile, cutting off storm formation and development.

If storms do form, they tend to do so before or after the summer monsoon season, when wind shear — winds moving at different directions at different levels of the atmosphere — is at its worst.

So the timing of Chapala and Megh isn’t unusual, but the short time between one storm and the other hasn’t been seen in the historical record, with high-quality data going back to 1990.

“In the historical record we’ve never seen two tropical cyclones spin up, especially one after the other, during this time of year,” Amato Evan, an atmospheric scientist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, said in email.

At its peak strength, Chapala had winds of about 155 mph, equivalent to a Category 4 hurricane. By wind speed, it was the second strongest storm ever recorded in the region, behind Cyclone Gonu in 2007. (By another measure, which takes into account a storm’s winds over its entire lifetime, Chapala was the strongest.)

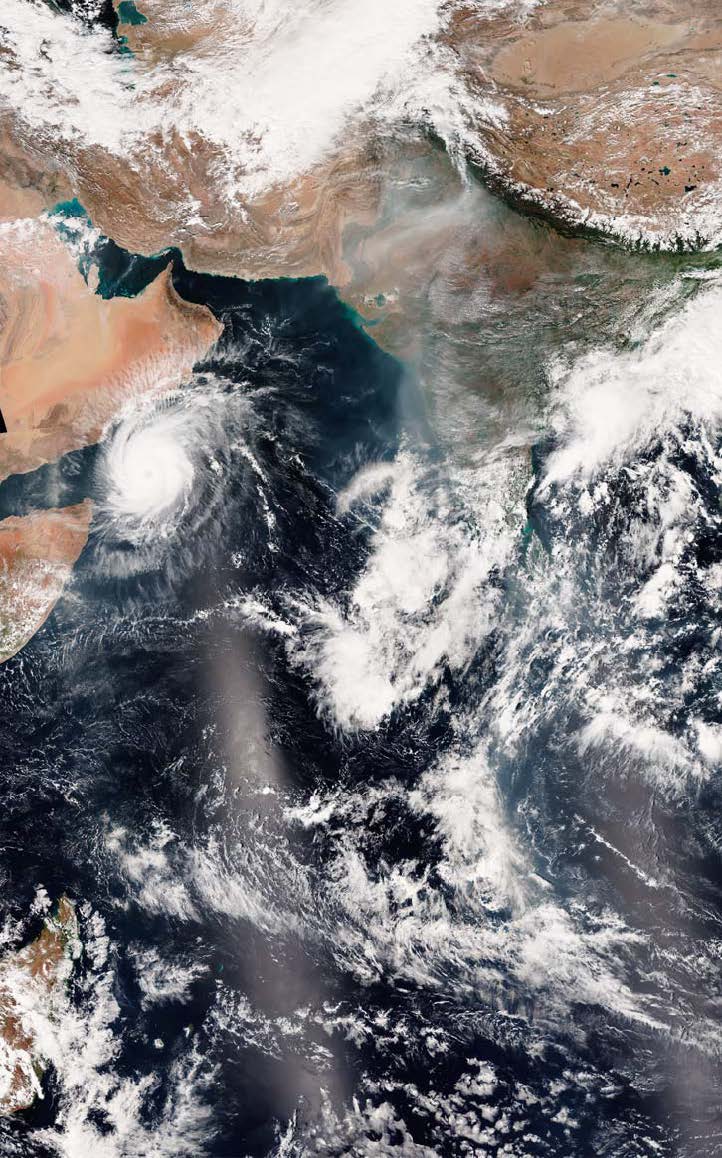

This photo shows a high definition visual of Cyclone Chapala November 1, 2015. Chapala made landfall on Tuesday November 2nd west of Mukalla. Right behind it you can see the formation of Cyclone Megh, which will make a direct hit on Yemen’s Socotra Island November 8th and make a final landfall in mainland Yemen on November 10th This is a photo taken from NOAA View Data Imagery, Environmental Visualization Laboratory http://www.nnvl.noaa.gov/

Chapala was able to reach such heights because it happened to encounter a particularly favorable environment, with wind patterns that actually encouraged its development. That let the storm take advantage of ocean waters with unusually high temperatures, even for the always-warm Arabian Sea.

Megh has also benefited from this conducive environment, though waters along its path weren’t quite as warm, thanks to the relatively cooler waters Chapala left in its wake, and it topped out Category 3 strength.

One reason winds may have been so favorable for both storms could be El Niño, the force that seems to behind so many trends this year. Monsoon winds in the region tend to be weaker during an El Niño, Suzana Camargo, a hurricane researcher at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, remarked in an email. “It's not clear, though, if we can obviously blame these storms on El Niño, as it would be important to do a more indepth analysis, but that's my suspicion,” she said.

These same conditions have also allowed for the development of another storm, in the Bay of Bengal. The last time there were storms in both areas simultaneously was 2010, hurricane researcher Philip Klotzbach, of Colorado State University, told Forbes.

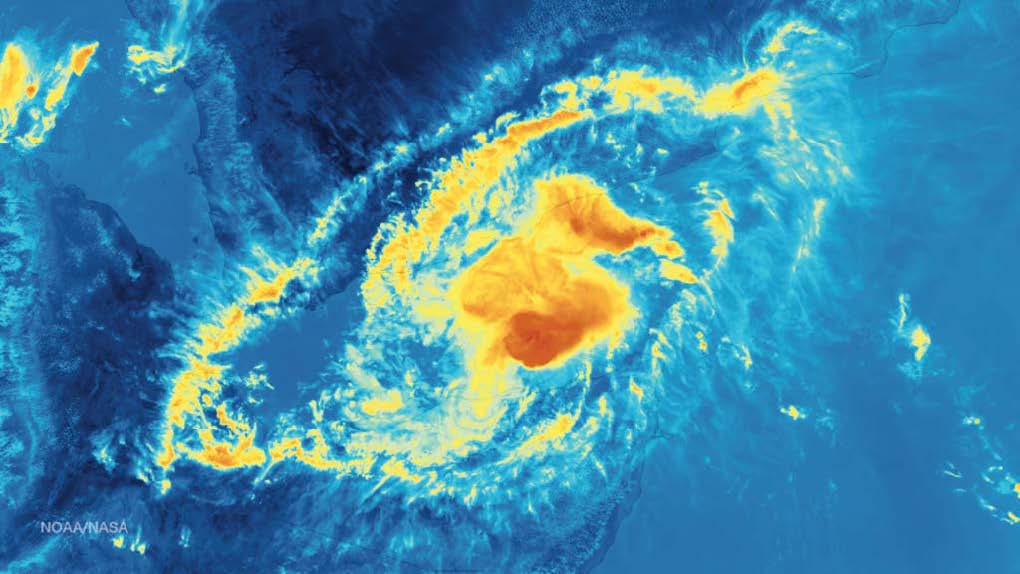

This infrared image was taken by Suomi NPP satellite’s VIIRS instrument around 1005Z on November 9, 2015 (Image: NOAA/NASA) tropical cyclone, Megh, Yemen, Oman, Gulf of Aden, NPP, VIIRS, 2015.11.09

Megh took a slightly more southerly path than Chapala, brushing the coast of Somalia as it headed toward landfall. That interaction with land, as well as dry air from the Arabian Peninsula, weakened the storm before it hit Yemen.

Reports about damage in the Aden area will likely take time to fully emerge, though the reinsurance firm Aon Benfield cited reports of widespread flooding and damage and at least two deaths on the island of Socotra, which was also hit hard by Chapala.

Rain and flooding are major concerns again with Megh as Yemen typically only sees about 2 inches of rain in a year. Chapala’s rains caused severe flooding in and around Mukalla — the impact was visible from satellites observing from space, which saw floodwaters near the coast and numerous wadis, or ephemeral streams, flush with water. Arabian Sea cyclone activity has generally received much less attention from researchers than busier basins, but this season could change that.

“This year will probably raise my interest in this area again,” said Camargo, who along with Evan conducted a survey of activity in the region in 2011.

Of the research that has been done, there are some potential forces that could be at play to allow for stronger Arabian Sea storms. Another study that involved Evan suggested that increased aerosol pollution could be allowing for more intensification of Arabian Sea storms.

“In the paper we speculated that the very thing we have right now (very strong cyclones occurring during the post-monsoon season) would be possible in the future as a result of increased pollution and lower wind shear,” Evan said.

Other research has suggested that climate change could lead to an increase in cyclone activity in the Arabian Sea, but a decrease in the Bay of Bengal. Research on such potential links is limited and requires further study, Camargo said.

Tropical Cyclone Chapala November 1, 2015 (Image: NOAA/NASA)

Content sharing agreement and written permissions to use this article were obtained prior to production for the sole use of the Mariners Weather Log. For more articles and related news go to: www.wxshift.com/news/ athompson@climatecentral.org

Back to top